Titan’s Icy Surface Just Broke a Fundamental Rule of Chemistry

By Chalmers University of Technology1 Comment7 Mins Read

FacebookTwitterPinterestTelegram

Share

Scientists have found that on Titan, substances that should remain separate can actually combine under freezing conditions.

NASA and Chalmers University researchers discovered that hydrogen cyanide can form stable crystals with methane and ethane, overturning a basic rule of chemistry. The finding offers new clues about how life’s essential molecules may have arisen in harsh, prebiotic environments.

Breaking the Rules of Chemistry on Titan

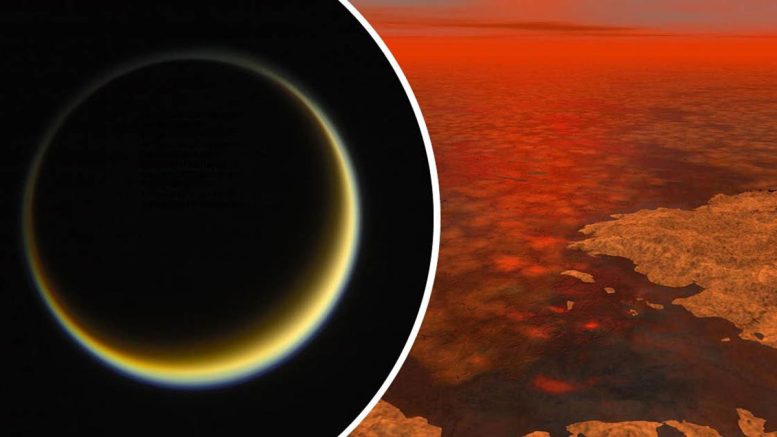

For decades, scientists have been captivated by Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, believing that its history could reveal how life began on Earth. The frigid world, wrapped in a thick atmosphere rich in nitrogen and methane, shares striking similarities with the conditions thought to have existed on our planet billions of years ago. By examining Titan’s chemistry and climate, researchers hope to uncover clues about the processes that paved the way for life to form.

Martin Rahm, an Associate Professor in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering at Chalmers University of Technology, has spent years exploring Titan’s complex chemistry. His team’s recent discovery, that certain polar and nonpolar substances[1] can actually combine under Titan’s freezing conditions, may provide valuable direction for future research on the moon.

“These are very exciting findings that can help us understand something on a very large scale, a moon as big as the planet Mercury,” he says.

New Insights Into Life’s Building Blocks

The team’s research, published in the journal PNAS, reveals that methane, ethane, and hydrogen cyanide—compounds found in abundance on Titan’s surface and in its atmosphere—can interact in ways scientists once thought impossible. The fact that hydrogen cyanide, a highly polar molecule, can form solid crystals with nonpolar substances such as methane and ethane is remarkable, since these materials normally remain separate, like oil and water.

“The discovery of the unexpected interaction between these substances could affect how we understand the Titan’s geology and its strange landscapes of lakes, seas and sand dunes. In addition, hydrogen cyanide is likely to play an important role in the abiotic creation of several of life’s building blocks, for example amino acids, which are used for the construction of proteins, and nucleobases, which are needed for the genetic code. So our work also contributes insights into chemistry before the emergence of life, and how it might proceed in extreme, inhospitable environments,” says Martin Rahm, who led the study.

NASA Collaboration Sparks Discovery

The background to the Chalmers study is an unanswered question about Titan: What happens to hydrogen cyanide after it is created in Titan’s atmosphere? Are there meters of it deposited on the surface or has it interacted or reacted with its surroundings in some way?

To seek the answer, a group at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California began conducting experiments in which they mixed hydrogen cyanide with methane and ethane at temperatures as low as 90 Kelvin (about -180 degrees Celsius). At these temperatures, hydrogen cyanide is a crystal, and methane and ethane are liquids.

When they studied such mixtures using laser spectroscopy, a method for examining materials and molecules at the atomic level, they found that the molecules were intact, but that something had still happened. To understand what, they contacted Martin Rahm’s research group at Chalmers, which had conducted extensive research into hydrogen cyanide.

“This led to an exciting theoretical and experimental collaboration between Chalmers and NASA. The question we asked ourselves was a bit crazy: Can the measurements be explained by a crystal structure in which methane or ethane is mixed with hydrogen cyanide? This contradicts a rule in chemistry, ‘like dissolves like’, which basically means that it should not be possible to combine these polar and nonpolar substances,” says Martin Rahm.

Expanding the Boundaries of Chemistry

The Chalmers researchers used large scale computer simulations to test thousands of different ways of organizing the molecules in the solid state, in search of answers. In their analysis, they found that hydrocarbons had penetrated the crystal lattice of hydrogen cyanide and formed stable new structures known as co-crystals.

“This can happen at very low temperatures, like those on Titan. Our calculations predicted not only that the unexpected mixtures are stable under Titan’s conditions, but also spectra of light that coincide well with NASA’s measurements,” he says.

The discovery challenges one of the best-known rules of chemistry, but Martin Rahm does not think it is time to rewrite the chemistry books.

“I see it as a nice example of when boundaries are moved in chemistry and a universally accepted rule does not always apply,” he says.

In 2034, NASA’s space probe Dragonfly is expected to reach Titan, with the aim of investigating what is on its surface. Until then, Martin Rahm and his colleagues plan to continue exploring hydrogen cyanide chemistry, partly in collaboration with NASA.

“Hydrogen cyanide is found in many places in the Universe, for example in large dust clouds, in planetary atmospheres and in comets. The findings of our study may help us understand what happens in other cold environments in space. And we may be able to find out if other nonpolar molecules can also enter the hydrogen cyanide crystals and, if so, what this might mean for the chemistry preceding the emergence of life,” he says.

More on Titan and Dragonfly

Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, is among the Solar System’s most unusual worlds – and it may share features with Earth’s early evolution. Titan is surrounded by a thick atmosphere composed mostly of nitrogen and methane, a composition that could resemble the atmosphere on Earth billions of years ago, before life emerged. Sunlight and other radiation from space cause these molecules to react with each other, which is why the moon is shrouded in a chemically complex, orange-colored haze of organic (i.e. carbon-rich) compounds. One of the main substances created in this way is hydrogen cyanide.

Titan’s extremely cold surface is home to lakes and rivers of liquid methane and ethane. It is the only other known place in our solar system, apart from Earth, where liquids form lakes on the surface. Titan has weather and seasons. There is wind, clouds form and it rains, albeit in the form of methane instead of water. Measurements also show that there is likely a large sea of liquid water many kilometers below the cold surface which, in principle, might harbor life.

In 2028, the US space agency NASA plans to launch the Dragonfly space probe, which is expected to reach Titan in 2034. The aim is to study prebiotic chemistry, the chemistry that precedes life, and to look for signs of life.

Notes

- About polar and nonpolar substances

Polar substances consist of molecules with an asymmetrical charge distribution (a positive side and a negative side), while nonpolar materials have a symmetrical charge distribution. Polar and nonpolar molecules rarely mix, because polar molecules preferentially attract one another via electrostatic interactions.

Du muss angemeldet sein, um einen Kommentar zu veröffentlichen.